Jazz is, or is supposed to be, a wild idiom, invented on the fly by trained professionals, a masterpiece by midnight. Certain ontological limits exist: Jazz is a form of music, made with instruments, by people. You can have any number of people, and any instrument you want, and still call it jazz. The aesthetic limits are narrower: at some point, free jazz becomes noisome avant-gardisme, the breaking of limits for its own sake, which is never not adolescent. Music does not have to be pleasant; it does have to express something, rather than nothing.

Paradoxically, one way to increase jazz’s area of operations has been to wed it to something simpler. Miles Davis saw Rock and Funk music as a way to give jazz a powerful bottom, enabling ever-wilder creations at the treble end. When the rhythm stays tight, you can dance whichever way you want. I can get through and even enjoy On the Corner precisely because I can always follow what the drums and the guitar are doing. It’s a lifeline in a noise machine.

James Chance (AKA James White) was another adopter of this approach. Unlike Miles, he hadn’t had a fully successful career before trying to bridge the two genres. And unlike Miles, he didn’t ease into it over the course of two albums before letting it burst forth from him. And most unlike Miles, he didn’t have a meteoric career as a result; he became notorious, an avant-punk provocateur, a white noise supremacist.

That last phrase isn’t mine, it’s Lester Bangs’, from an article of same name, running down the Punk First Wave as being racially insensitive. There’s a lot of ammunition for this accusation; the whole point of punk was to be outrageous, and fascist symbols and racial slurs are a cheap and easy way to achieve that goal. Well, easy definitely, not necessarily cheap, because as soon as someone notices, they’re going to ask how much of this is a pose and how much the truth. Bangs, who came up out of the sixties, who loves free jazz and garage rock in equal amounts, has no problem saying “Hey, let’s cool it with the anti-semitic remarks”, and the intellectual honesty to admit that he’s thrown forbidden words around without thinking about it.

So when Lester writes the following…

James Chance of the Contortions used to come up to Bob Quine pleading for Bob to play him his Charlie Parker records. Now, in a New York Rocker interview, James dismisses the magical qualities of black music as “just a bunch of nigger bullshit.” Why? Because James wants to be famous, and ripping off Albert Ayler isn’t enough. My, isn’t he outrageous? (“He’s got the shtick down,” said Danny Fields, stifling a yawn, when they put James on the cover of Soho Weekly News.)

Lester Bangs, “The White Noise Supremacists”, The Village Voice, 1979

…I assume he’s right on the facts, that James said that at some point. However, I wish to point out the fact that the quoted Danny Fields was as much a provocateur as anyone at CBGB’s. More, even, because he managed to troll half the country.

But my publisher at Datebook had bought Maureen Cleave’s interviews with The Beatles from the Evening Standard, and I thought it might be a good idea to take these interviews and chop them up to use in the magazine. I found a Paul McCartney quote where he described America as “a lousy country where anyone black is a dirty nigger’, and I thought ‘Oh, that looks like a headline to me.’ And then there was another quote from John Lennon saying ‘I don’t know which will go first, rock n’ roll or Christianity’, which I thought was interesting. So I ran maybe 800 words in Datebook from those articles. And deep in there was Lennon’s quote about The Beatles being more popular than Jesus. And then some mother in Alabama read that in her daughter’s magazine, and took it to a local radio station, and some DJ who hated that he’d been forced to play these Beatles records started a crusade in this swampy redneck town encouraging listeners to bring their Beatles records and pictures down to the local church and he’d set them all on fire…

…And then because The Beatles were getting death threats from the KKK and whoever, John Lennon was summoned to hold a press conference in Chicago to ask about his Jesus comments – which must have confused him given that he’d given that interview eight months previously and no-one in England cared. After the last concert on that tour, The Beatles announced they would never play again, and they never did. And I thought ‘Hmmm, I wonder how much part my article had in this? What fun to make such mischief!’”

Paul Brannigan, “How Danny Fields Changed Music Forever“, Louder Sound

Indeed, such fun to piss off people you don’t know and don’t like, and cause public outrage against a rock and roll band, so you can sell more copies of… Datebook. It’s fine when you’re doing it to swampy rednecks, you see, everyone hates them and they deserve it. You’re such a hero.

The point of this sidebar isn’t just to stick fingers in the eye of an overrated scene-kid who was equally mediocre at being the Doors’ publicist and the Stooges’ manager, but to point out that what gets left out of the story is determinative. Bangs never sat down with James Chance to ask his thoughts on black music, white music or racial harmony, relying instead on people he knew and was friendly with (mostly Richard Hell, Bob Quine, and Ivan Julian, who were all in the Voidoids). It took Pitchfork, in 2003, to actually ask:

If you are a white person doing black music, you have to come to terms with it, confront it in some way. You can just be an imitator, which a lot of white people do, or you can try to find something original in it. If you’re going to do that, you…have to accept your whiteness instead of just…a lot of those loft-jazz musicians just rejected their idea of being white and tried to be as black as possible, which didn’t ring true at all. It just made them look silly. They didn’t garner respect from black people for being like that. So I decided it would be much better to flaunt being white, which made much more of a statement at the time. Probably still does…

…At that time in New York, there was a lot of racial tension in the air. A lot of the black kind of street-type people had a very hostile attitude at that time towards any and all whites. You couldn’t miss it, it was very obvious. When I was in Milwaukee, I actually lived in the middle of the ghetto for a while. I used to sit in at these black after-hours’ clubs, these hardcore places. Pimps would be passed out on the table after snorting coke all night and drinking whiskey, gambling and backgammon. I used to also hang out at this stripper bar, where almost all the dancers were black, and I would hang out with these black strippers a lot and their boyfriends and they were all pretty free and easy. I got along with them pretty well. It was no big deal that I was white. But when I came to New York, there was much more of a racial separation here. There were a lot of people on the rock scene that were pretty racist too, they were throwing the word “nigger” around. I took a lot of shit from some people for bringing in black music, much less liking it.

James Chance, Interview by Pitchfork, 2003

The Narrative, it has become complicated. Note how modern this sounds: coming to terms with his identity, owning it rather than hiding it, and doing his best to add something to the music, rather than just imitating it. The guy knows he’s a white man in a genre heavily dominated by blacks (which doesn’t make it ontologically black music, white people have been involved in it from the beginning, and the genre derives as much from European as African idioms), so he leans into it. And he seems to have been as unimpressed by the use of a Certain Slur as Bangs was. It raises the question of whether Bangs actually heard Chance say what he attributed to him, or if a Quotation Telephone Game occurred:

JW There was a big backlash, against me personally. Some of the musicians in that band said things about me that were mostly lies and were totally malicious . . .

James Chance, Interview by Tod Wizon, Bomb Magazine, 1991

This doesn’t prove anything. Chance has a reputation of being a hostile performer, going out of his way to provoke audiences, up to and past the point of physical altercation. It is therefore entirely plausible that the guy dropped N-bombs casually, inasmuch as doing that in the 1970’s created nowhere near as much social backlash it does today. As said before, getting a rise out of people was part of the schtick, part of the act, even if it came from a genuine place.

TW That’s some song. Someone said to me, a little while ago, “You can’t create from hatred. You can’t create from negativity. You have to create from love.”

JW Bullshit.

TW A total fallacy. It has to be from both, to the extreme of both.

JW What I’d say is, there is a certain joy just in the act of creation, which is always there just by its very nature. But certainly, when I started with the Contortions, the main thing that was driving me was hatred. This hating the world so much and wanting to show them what I thought of them and make them like it. That is a really strong driving force.

TW I hate to say it, but I get joy from “I Don’t Want To Be Happy.” Something deep in me, clicks. That emotion brings me to a new plane of realization in my life; new planes of experience of listening. Sometimes you feel your aloneness is assuaged by hearing something like that. In a perverse way, it’s very comforting.

ibid.

Here at last we confront the aesthetics. What is the value of turning entertainment on its head? Making a feelgood time into a fistfight? There’s a long tradition of it, from jazz artists who turned their back to the audience on down. Sometimes the artificiality of the artist-audience relationship merits the deconstruction.

The key word is sometimes. While there’s something bracing about a jazz saxophonist picking fights with a paying audience, something few rockers have ever had the gumption for (what would James have done at Altamont?), it’s not the way to make lasting art. The essence of Art is some form of communication between artist and audience. That communication doesn’t have to be chummy, but it does have to convey something that the audience can hear and accept. Otherwise you’re just flailing like an idiot, and everyone laughs at you.

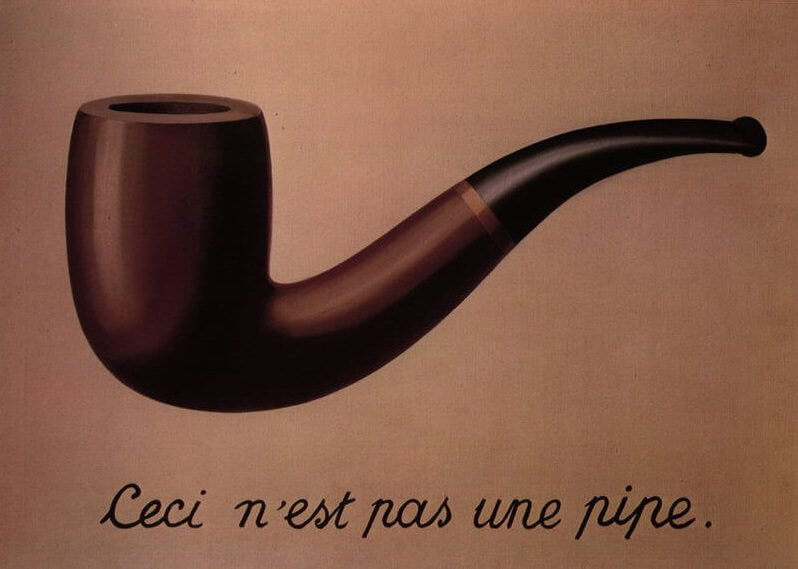

This is the problem the avant-garde has had for a while. They keep treating their potential audience with contemptuous evasion, and then acting surprised that they’re not getting through. We’re well beyond The Treachery of Images, which while provocative and profound, was also accessible. It takes at most a sentence explanation to convey the point, and most people will say “ohhhhhhh… good point.”

But who the hell wants to go to a concert to get punched? For some bored dilettantes or anger addicts, that might be a draw, but diminishing returns will set in fast and undo the very inversion you’re trying to create. And then you’ve made a box that you can’t escape from.

JW I was the only musician in New York at that time, that made both the jazz scene and CBGB’s, Max’s scene, the only one who actually played in both scenes. Some other musicians listened to a lot of jazz, but I was the only one who actually went to jazz clubs. I was the first one to put those elements together. It really pisses me off that I don’t get the credit and respect for what I’ve done. I feel that’s only correct. You asked me yesterday why I haven’t made a record for seven years. One of the reasons is that my experiences in the music business have made me so disgusted and disillusioned that I just refuse to deal with it. I just will not be treated the way certain people have treated me. I refuse to even take the chance that someone will treat me like that. So I won’t even talk to somebody in the music business, unless I know them, and know what their attitude will be toward me. The thing that really disillusioned me—it wasn’t that I expected people to be wonderful—but I didn’t realize how much people were motivated by pure envy and maliciousness, to the point where they’re willing to hurt their own interests in order to fuck someone over. I just refuse to be put in a position where I can be treated in that way. I’d rather not even work at all.

ibid.

And there it is. You can only be an anti-star so long before you either remake stardom in your image or you collapse into an artistic black hole. You need to find an audience that not only can pick up what you’re putting down, but wants to. You need to give them something they want.

So, then, why is this song stuck in my head? Because the fusion I mentioned somewhere up top works. The rhythm is rocksteady, and the sax squeeeeels are irruptive and disciplined. I don’t get sick of it, like I do with Ornette/Ayler-style free jazz, twenty-minutes-of-blare. I am flying with one ear, and rooted with the other, like any good ape-angel should be.

No, it won’t be everyone’s cup of tea. But if you wondered what the hell happened to Jazz after the Free and Fusion movements ran their course, this might be a spot to stop and ponder what might have been.

[…] return to the questions dogging our discussion of James Chance, who, no one should be surprised, to learn, was very much a No Waver whose work appears on No New […]