The mighty always fall.

There’s a moment, early in the recent Rolling Stones Documentary Crossfire Hurricane, where Mick Jagger discusses the level of truth to the band’s bad-boy image, as marketed by manager/impresario Andrew Loog Oldham:

“When you cast actors for a part, you look to find actors suitable for the part. We were actors suitable for the part.”

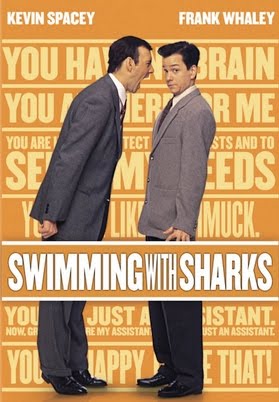

Back in the 90’s, a movie having Kevin Spacey in it was a signal to hip-pretending college kids that unpleasant truths and vicious twists were on offer. This culminated in his Oscar turn in American Beauty, whereupon, in the opinion of this author, he largely vanished from the big screen, farting about in cash-taking exercises until laying down a marker on the Streaming Age with his star turn on House of Cards. But in that run of 90’s films, he was always playing a heavy, and always bringing an illuminative cruelty to the story. Consider Keyzer Soze in The Usual Suspects, playing a sap to cover his demonic mastermind of a massacre. Consider John Doe in Se7en, pronouncing doom on mankind with Satanic authority.

And now that we know that the actual man spent all that time as a real-life predator, we must assume that the actor was suitable for the part. And that wisdom is fine so far as it goes. But given that real-life predators have been, are being, outed in vast sweep throughout that industry, one must begin to wonder what it is that keeps that particular system so full of sociopaths, how it became so unremarkable that sex is the commodity to be offered as continuous tribute to the powers-that-be. It strikes me that Spacey and Weinstein and the rest didn’t act as they did, with no expectation of consequences, for no reason. Something in Hollywood has been wrong for a very long time.

And as it happens, in 1994 Kevin Spacey made a film about that.

The marketing for it is all wrong. It’s sold as a black comedy, which it absolutely is not. There are moments of cruel humor, but mostly this plays like a straight-up, almost horror-fim of a naive twerp brutalized and corrupted by the enforced sycophancy of the Hollywood system. He rebels against this system, holds his boss hostage with a gun, and beats and tortures him with the kind of vengeance only a slave can imagine. You take away a man’s freedom, and you make of him a beast.

This was one of the first movies I ever saw that begins at the end of the story, with a body wheeled out into a ambulance. You don’t realize until the very final scene whose body it is, and that was a twist that got the attention of 17-year-old me, and a good few of my generation. For Generation X has long had operant in its philosophical DNA the highly Puritanical notion of Total Depravity – that there is not one righteous in this world, not one. If you grew up in the 70’s and 80’s, when New York City was a slaughterhouse, when teen pregnancy was on the rise, when mindless sex and depraved violence were the dominant theme in music and movies alike, you would have had a hard time escaping it. This idea runs through Se7en and The Usual Suspects, and rears its head also in Reservoir Dogs and Trainspotting as well. There is nothing to believe in, no institution to trust. The Cops are on the take. The President is a crook. The Archbishop is hiding pedophiles.

Consequently, many of us liked movies where the bad guys won, because at least these – unlike all those idiot self-esteem coaches our schools inflicted on us – were telling us the truth. There was nothing more inane in my middle school days than to have some kindly public speaker assure us how wonderful we were and that if we believed in ourselves anything was possible, and then to go back to the regular school day when the same bullies tortured the same kids. No amount of believing in myself spared me the hard reality that humans divide themselves into tribes, establish outcasts, and cast aside every part of their God-given reason to maintain their Status within the System. That was reality. Everything else was perfume.

Everyone Lies. Good Guys Lose. And Love does not conquer all.

-Swimming With Sharks

Now, as it happens, that’s not the whole story. No story is the whole story, save that in the mind of God. Darkness gives way to light. School gives way to Adult Life. And Kevin Spacey’s life indicates that no one gets away with it forever. But Swimming With Sharks does illuminate the lust for power, and the eagerness to abuse that power, that sits at the heart of Hollywood.

And the time of it’s creation surely informed the attitudes it illuminates. Back in October, The Other McCain gave us some useful mis-en-scene for Spacey’s alleged assault of Anthony Rapp in 1986:

It was the ’80s, and it was New York, a city out of control, lawless and corrupt, and what did Kevin Spacey think when Anthony Rapp came to his party and stayed after all the other guests had left? Was he worried about the law? Don’t be ridiculous. Cops in New York in 1986 were dealing with an annual murder rate (1,907 victims, 10.7 per 100,000 residents) more than triple what it was in 2016 (630 victims, 3.2 per 100,000 residents). In an average week of 1986, more than 35 people in New York were murdered, not to mention the more than 5,000 rapes and 90,000 robberies that year. What were the chances, amid this carnival of violence, that the NYPD would find time to investigate a popular young actor for inappropriate behavior with a teenager? Approximately zero.

1994 was the beginning of the shift away from that, but it wasn’t apparent at the time. At the time, post-early-90’s recession, in the year of Kurt Cobain’s self-hating suicide, things still looked very dark indeed. So when the turn occurs in Swimming With Sharks, Spacey’s character preaches the reality of surviving in a cruel world:

This scene is the black heart of Swimming with Sharks, and it has become almost impossible to watch Spacey do it and not read it as a confession of his own personal truth. If this man felt entitled to a piece of 14-year-old boy tail in 1986, and was certain that he could get away with it, how can that not inform his reading of this scene shot eight years later? When I heard about the various allegations against Spacey, how he would engage in odd sexual power-plays on set (grabbing a man by the crotch and saying “This constitutes ownership”), my mind went immediately to this scene. The actor was not just suitable to the part; he lived it.

On a larger level, this piece of art from 1994 underlines the reality that Hollywood has always been this way, that Weinstein and Spacey and everyone else are just the current manifestations of an industry in which youth and beauty and popularity and every expression of the human soul is a commodity sold by the theater seat. Entertainment is high-reward, high-risk: and the wisdom of William Goldman: “Nobody knows anything”, means that you will lose money just as often as you gain it (even a piece of a sure-thing like Solo: a Star Wars Story, is looking like a big fat pile of disappointment for Disney). Consequently, someone who pays his dues and has a track record of bringing home the bacon gets a pass for whatever swinery happens behind closed doors.

Until now?

Maybe. Maybe a younger generation absorbs the idea that in the internet age, nothing stays hidden forever, and maybe the powerful and successful among them observe that despicable behavior can come back to bite them. Certainly the tolerance for such behavior has lessened in the last thirty years.

But so long as the hungry need the favor of the powerful, its’ hard to believe the casting couch will be empty.

[…] “The Darkness of Kevin Spacey: Swimming With Sharks and How Hollywood Breeds Monsters“ […]